In recent years, the slogan “Artificial intelligence in medicine” has ceased to be just a weighty headline for futuristic articles. Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly entering everyday medical practice: it analyzes radiological images, predicts disease risks and even communicates with patients as a chatbot.

The replacement of specialists by machines and technology is a real concern in the medical community, both among students and experienced clinicians. But do automation and AI really have to pose a threat to the medical profession? You will read about this in this article.

Artificial intelligence in healthcare is not the song of the future. These are functional solutions that support doctors in many areas.

Radiology is the most advanced area of AI implementations. Algorithms that analyze images, learn on millions of cases, thanks to which they can detect pathological changes with great precision on X-ray, CT or MR images. An example is the “AI-Rad Companion” system from Siemens Healthineers [8], which supports the analysis of chest tomography, automatically identifying changes suspected of cancer, rib fractures or emphysema. This solution shortens the description time and increases the sensitivity of detection of pathological changes.

In primary care, AI supports the selection of symptoms and the decision on the need for a medical consultation. The Infermedica system and other “symptom-checker” applications analyze clinical images from big data sets and then present possible diagnoses or next steps. The doctor can use them to select and educate patients [5].

Artificial intelligence supports oncologists in the selection of targeted therapy based on genome analysis, histopathology and clinical data. The PathAI program achieves relevance comparable to pathomorphologists [9]. The Perception tool uses single-cell RNA-seq data to predict drug responses [6]. The “Enlight-Deep-PT” model presented in July 2024, uses images of tumors without the need for sequencing, helps predict the effectiveness of therapy, thus speeding up therapeutic decisions [6].

We do not rely solely on hard data, we also look through the lens of our own experiences and observations. We see a future in which the doctor is not replaced by artificial intelligence, but acquires a new, even more important role: interpreter, guide and trustee of the patient.

Artificial intelligence will not take away the work of those doctors who can adapt to it, understand its potential and limitations, and use it as a tool to increase the effectiveness of treatment. However, over time, it can replace those who do not want to develop, do not update knowledge and resist change.

Technology itself is not a threat. The danger is a lack of understanding of how it works, what limitations it has and where it can fail. AI operates on the basis of data, often reduced, simplified and devoid of context. It does not take into account the nuances of talking with the patient, his family history, preferences, fears. He will not feel the irony, will not recognize facial expressions, will not explain the meaning of palliative therapy. Therefore, at the center of the relationship with the patient still remains the human being, empathic, attentive and able to give meaning to even the most difficult therapeutic decisions.

It becomes essential to know the basics of machine learning and artificial intelligence in the medical context. This includes distinguishing between supervised and unsupervised models, understanding indicators of predictive quality (such as sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value, AUC — area under the curve), and awareness of phenomena such as data bias. A doctor who uses AI-based decision support should be able to ask critical questions:

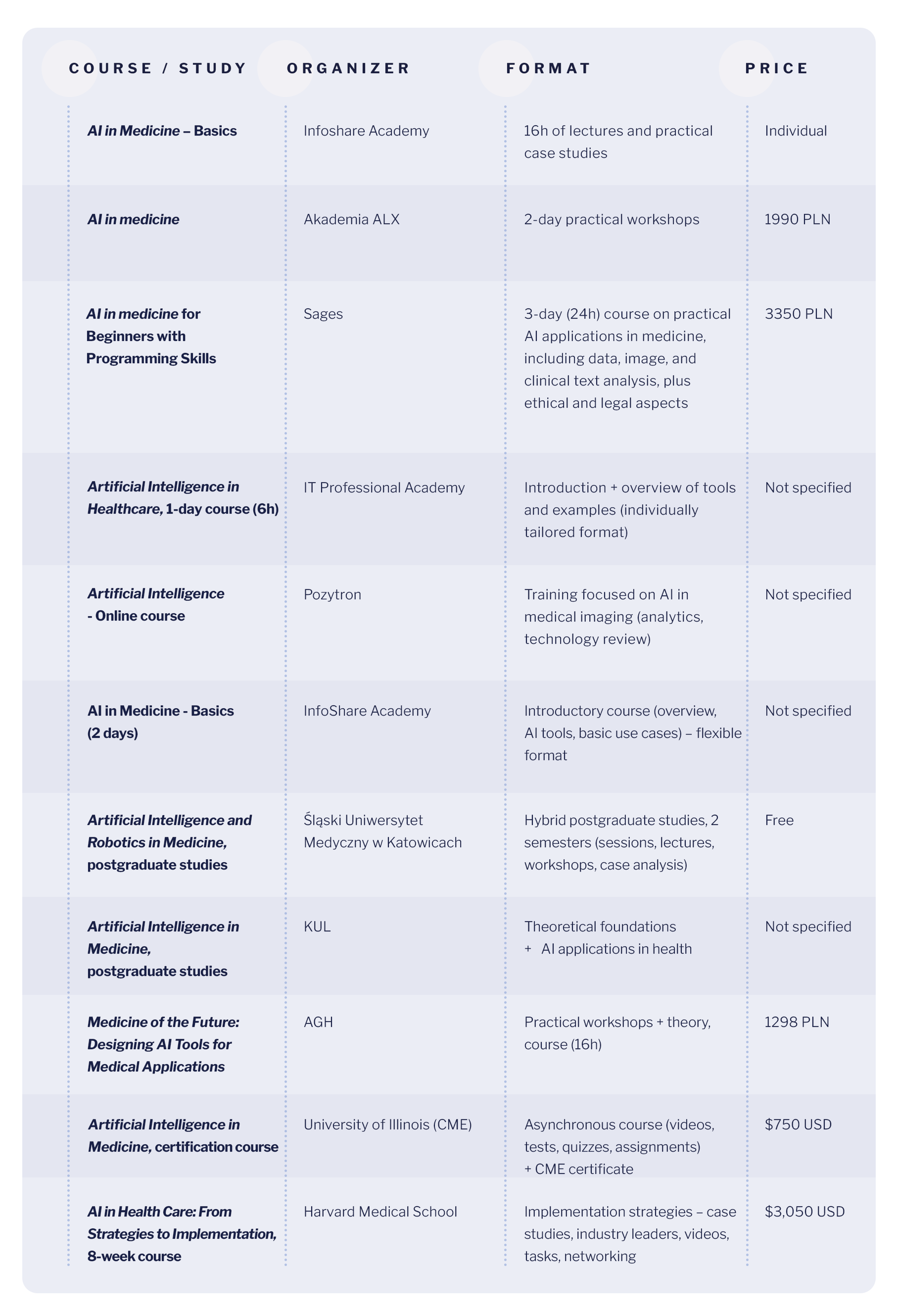

Where can you get such skills? Below is a list of courses for doctors, medical and pharmaceutical professionals and health managers on AI in medicine:

Patients increasingly come to the office after prior contact with a chatbot, a symptom-checker application or a generative language model. In such situations, the doctor must not only be able to interpret the previous AI suggestions, but above all, explain in an understandable and empathetic way to the patient that the result generated by the algorithm is not a definitive diagnosis, but only a hypothesis that needs to be verified in an individual context. The modern clinical relationship is no longer based solely on the transmission of information, but increasingly on the rebuilding of trust in an environment saturated with uncertain and unverified sources of knowledge. The ability to talk in the context of “digital misinformation” is becoming a key clinical competence of the 21st century. Below is a summary of recommended courses, books and educational programs for physicians that help develop the ability to communicate with the patient in the face of digital misinformation:

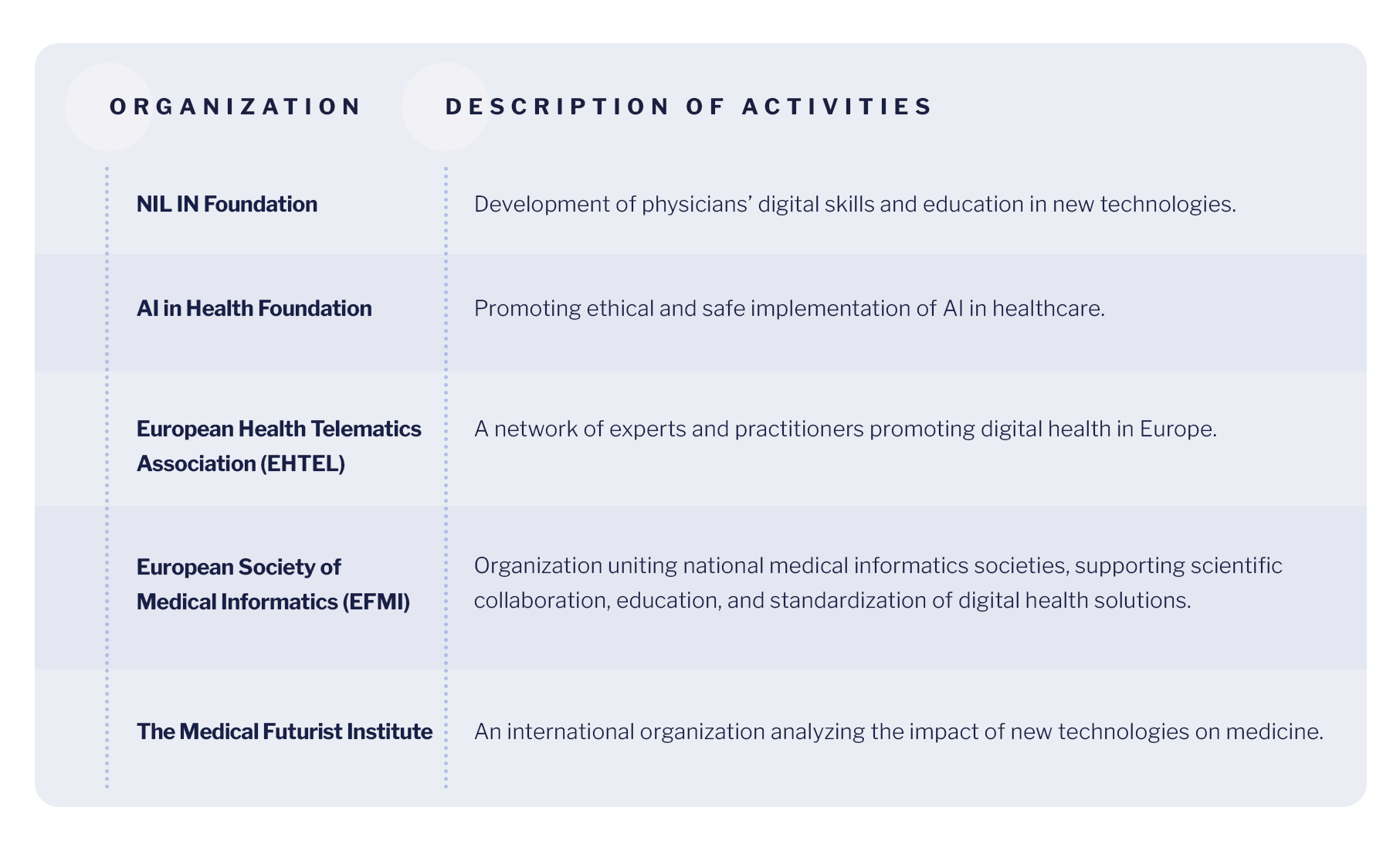

The third pillar of adaptation to the reality of digital medicine is the active participation of doctors in the process of designing, implementing and evaluating AI-based tools. The presence of representatives of medical professions in the creation of clinical systems guarantees that they will take into account the realities of work in healthcare institutions, the needs of patients and the specifics of the work of therapeutic teams. In turn, at the level of academic education, it is necessary that the foundations of the operation and application of AI be included in the training programs of doctors not as a technical element, but as an integral part of professional professionalism. A growing number of initiatives are enabling physicians to engage in shaping the digital future of healthcare, both nationally and internationally:

Understanding how the decision support algorithm works is becoming as important today as knowing the principles of EBM (evidence based medicine), because without this knowledge, the doctor will not be able to assess when AI can be relied on and when its recommendations should be challenged. By engaging in such initiatives, specialists can not only develop their own competencies, but also have a real impact on the direction in which digital medicine is headed.

In the book Deep Medicine, American cardiologist and visionary of digital medicine, Dr. Eric Topol, puts forward an important thesis: artificial intelligence will not take away the doctor's job. On the contrary, it can restore to him what is most valuable in his profession: time, the relationship with the patient and the depth of clinical thinking.

Topol argues that modern medicine has become dehumanized. The doctor spends only a dozen minutes per patient today, a significant part of which is absorbed by electronic documentation and administrative tasks. The patient becomes a record in the system, and the doctor, the operator of the keyboard. In this context, artificial intelligence appears not as a threat, but as a a tool to “regain humanity” in medicine.

Topol notes that algorithms can effectively take on repetitive tasks: image analysis, documentation search, consultation summaries, or risk prediction based on numerical data. But there are three areas where AI has no chance to replace a doctor:

Eric Topol does not postulate medicine without doctors. On the contrary, he advocates deep medicine (medecine), in which the doctor, supported by AI, recovers the meaning of his work. It's not about competition, it's about synergy between man and machine, where man sets the direction and the machine supports the decision.

Artificial intelligence will not take away the work of those doctors who can adapt to it, understand its potential and limitations, and use it as a tool to increase the effectiveness of treatment. However, over time, it can replace those who do not want to develop, do not update knowledge and resist change.

It is not technology that defines the future of the profession, but the way in which man interacts with it. The future of medicine does not belong to machines. The future of medicine belongs to doctors who can work with machines for the benefit of the patient. So the question is no longer: Will AI take my job?, but: What can I do today to make my AI work even better tomorrow?