Artificial intelligence (AI) is gaining more and more popularity in all areas of life. It is not surprising, therefore, that it is also becoming more and more present in health care. In medicine, it is already used in a wide range: from support in the creation of medical records, through diagnostics [2] and the discovery of new drugs [3], to research review, education, communication with the patient, support in therapy [1] and the provision of personalized therapeutic suggestions [5].

In this article, we analyze the key differences between a doctor and AI - not to value them, but to understand how to effectively collaborate with technology while maintaining full responsibility, patient relationship and patient safety.

In public debate, AI is often treated as a single phenomenon. In fact, this is a wide spectrum of tools - from simple text assistants to advanced clinical models that have passed rigorous validation. AI is a general category of technologies that can create new content - text, image, sound, video, code. Among them we distinguish, among others, [8]:

In medicine, however, two main types of AI models dominate:

An example of language models used in healthcare is Google's Med-Palm, which specializes in answering complex medical questions and synthesizing information from textual and image data, such as X-rays.

As for the second group - analytical models - they are used for imaging diagnostics. These are specialized AI models (often based on deep learning) that can analyze medical images (e.g., X-ray, CT, MRI, ultrasound) with a precision comparable to or superior to clinical experts. An example is the SLIVit model developed by UCLA [9], which analyzes 3D images of various modalities and models used to automatically classify and detect lesions based on images (e.g., in radiology, dermatology, pathomorphology, cardiology).

Unlike the doctor, AI models do not understand the meaning of their own answers - they only operate on statistical patterns. One of the most fundamental differences between a doctor and AI systems is precisely the ability to metacognitions - awareness of one's own ignorance. The doctor knows his responsibility. He knows that every clinical decision has consequences - not only medical, but also human, relational and legal. AI does not have this awareness. He doesn't know the patient, he doesn't understand the context, he doesn't know when to say “I don't know.”

AI systems — even when they don't know the answer — will always generate it with full conviction, without signaling uncertainty. This is what leads to the so-called. Hallucinations [7] - creating content that sounds believable but is completely untrue. Hallucination is not an intentional error, but a consequence of model construction. A gap in the data is enough for the system to “prove” the missing elements - by inventing studies, protocols or sources.

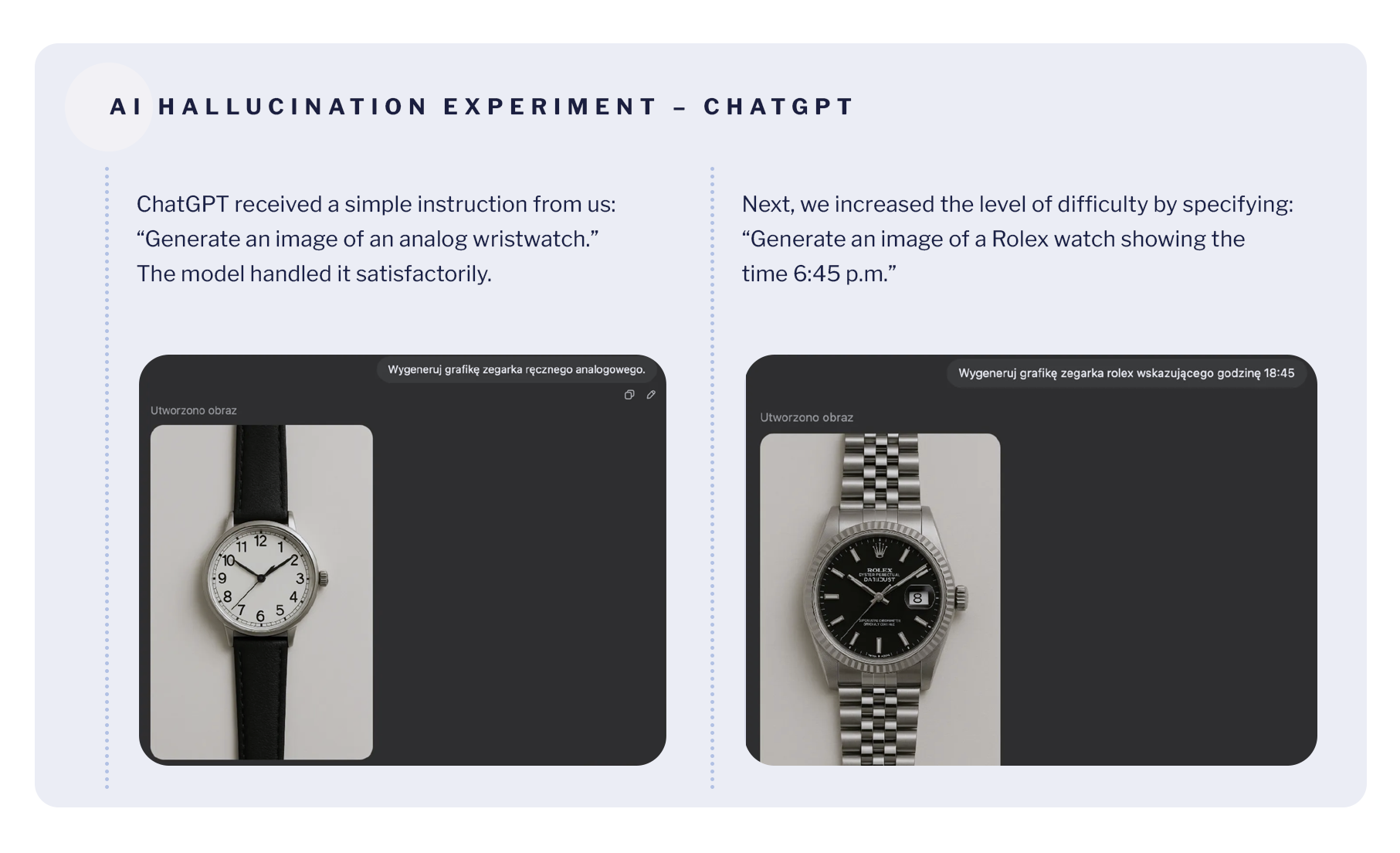

Research indicates that language models such as GPT-4 can confidently cite non-existent sources, invent research, or provide unverified data [7]. This was illustrated in detail in the watch image generation experiment. We ran a simple test in one of the most popular language models - ChatGPT - to see how this tool copes with the execution of the basic command. Here are the results of our test:

This revealed a typical problem of language models - they answer with complete certainty even when they are wrong, without signaling any doubts.

This is an image experiment, but an analogous mechanism works in the generation of medical content - the model can “invent” non-existent procedures or studies with just as much confidence. In medicine, where a false sense of confidence can be dangerous, it poses a serious threat. This can be especially harmful in a situation where erroneous information affects the therapeutic decisions of the doctor and the patient does not have the tools to verify them [7].

Therefore, AI should be considered as a tool that requires the conscious control and caution of you, as a doctor - an active, responsible user who knows when to distrust and can verify any proposal or information.

AI models analyze data, but do not know the context in which your patient lives. They do not take into account family relationships, emotional challenges, personal stories or nuances of contact. They don't see a man - they only see the code.

You have access to more than just data: relationships, conversations, experiences. It is the relational context that can be crucial in clinical decision making — and cannot be fully conveyed to the algorithm.

AI doesn't understand a situation where a patient says “nothing works anymore” or “I'm afraid it's cancer.” You - yes. You see the reactions of patients, their facial expressions, microinteractions. You know their history, so it's easier to recognize when they feel anxious, scared, or frightened by the diagnosis.

Even if AI generates relevant suggestions, it is never responsible for their consequences - legal, ethical, professional.

It is you who remains the author of the decision, regardless of which tool you used AI does not know the consequences of its “answers”. He does not participate in the conversation with the patient. AI is only a tool, not an entity capable of bearing the consequences of its “decisions”.

Therefore, AI can be your assistant - but it is you who are present with the patient, with the responsibility of this relationship.

The doctor-patient relationship is based on trust. It is not only competence, but also presence, mindfulness and empathy - especially in situations of uncertainty. The AI can simulate kindness in a text, but it will not respond to silence, notice a breaking voice, or take up a topic that is difficult for the patient to pronounce.

It is you who create an atmosphere that gives the patient a sense of security. AI has no intention, emotion, or relational responsibility.

Language models can generate text instantly. However, most generative applications of AI in healthcare are based on models whose data are based on unfiltered internet data [6]. This means that the models do not know if what they are quoting comes from a real source. They have no awareness that something may be imprecise, outdated, or simply non-existent.

You who use AI to create content - for example for a patient for educational content - should always check what is finally communicated. AI can write text very quickly and seemingly efficiently, but only a human can do it responsibly.

Most of the available AI models operate outside the EU and do not comply with the requirements of the GDPR. Sending medical data to an AI tool can mean a permanent loss of control over it. And it is worth remembering that AI does not understand what sensitive data is. As a result, he also does not understand what it means to violate someone's privacy.

You, on the other hand, act on the basis of specific regulations, but also on professional ethics. You know that data isn't just information — it's the personal stories of people who trusted you.

AI never - no matter how strongly developed - bears no legal or moral responsibility. Even if the model suggests an action that seems sensible, it is you who make the decision - and you are responsible for it to the patient, the law, professional ethics.

The responsible use of AI means not only knowing its possibilities, but also the limits that the crossing of which can put the patient, the doctor and the relationship between them at risk.. Used responsibly, they can free up time, support text analysis, improve communication with the patient, so it is worth using it for:

At the same time, we strongly do not recommend using AI to:

ang.png)

Ethical risks (such as unreliability, lack of accountability, bias in algorithm performance or privacy violations), as well as technical risks (such as data loss, distortion or lack of access), must be addressed with people's needs, security and responsibility in mind [7].

New technologies are changing medicine. But even the most advanced AI model will not replace the doctor. Because the differences are fundamental.

AI is getting better, but it's not replacing relationships. He doesn't make decisions. It bears no consequences. And he doesn't know your patient. Therefore, your role remains irreplaceable. AI can be your support and worth using during your daily practice - but only if you remain its active user, not a passive recipient. When you can use it like any other tool: with competence, responsibility and a healthy distance.

therefore Your presence, awareness and decisions remain key. AI can be your assistant. But you are the author and guide in the relationship with the patient.

[1] Eysenbach G., The Role of ChatGPT, Generative Language Models, and Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: A Conversation With ChatGPT and a Call for Papers, JMIR Med Educ 2023;9:e46885,, DOI: 10.2196/46885, https://mededu.jmir.org/2023/1/e46885

[2] E.J.T. is supported by NIH UM1TR004407 grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. He is on the Dexcom board of directors and serves as an adviser to Tempus Labs, Illumina, Pheno.AI, and Abridge. [https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adk6139]

[3] Xiangxiang Zeng, Fei Wang, Yuan Luo, Seung-gu Kang, Jian Tang, Felice C. Lightstone, Evandro F. Fang, Wendy Cornell, Ruth Nussinov, Feixiong Cheng, Deep generative molecular design reshapes drug discovery, Cell Reports Medicine, Volume 3, Issue 12, 2022, 100794, ISSN 2666-3791, [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100794.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666379122003494]

[4] Jiang, S., Hu, J., Wood, K. L., and Luo, J. (September 9, 2021). Data-Driven Design-By-Analogy: State-of-the-Art and Future Directions., ASME. J. Mech. Des. February 2022; 144(2): 020801. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4051681

[5] Javaid, Abid Haleem, Ravi Pratap Singh, ChatGPT for healthcare services: An emerging stage for an innovative perspective, BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2023, 100105, ISSN 2772-4859, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbench.2023.100105, [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772485923000224]

[6] Harrer S., Attention is not all you need: the complicated case of ethically using large language models in healthcare and medicine, BioMedicine, Volume 90, 104512, [https://www.thelancet.com/journals/ebiom/article/PIIS2352-3964(23)00077-4/fulltext]

[7] Chen Y., Esmaeilzadeh P., Generative AI in Medical Practice: In-Depth Exploration of Privacy and Security Challenges J Med Internet Res, 2024;26:e53008, doi: 10.2196/53008, PMID: 38457208, PMCID: 10960211, [https://www.jmir.org/2024/1/e53008/?utm]

[8] Zhang, P., & Kamel Boulos, M. N. (2023). Generative AI in Medicine and Healthcare: Promises, Opportunities and Challenges. Future Internet, 15(9), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15090286, [https://www.mdpi.com/1999-5903/15/9/286]

[9] Avram O, Durmus B, Rakocz N, Corradetti G, An U, Nitalla MG, Rudas A, Wakatsuki Y, Hirabayashi K, Velaga S, Tiosano L, Corvi F, Verma A, Karamat A, Lindenberg S, Oncel D, Almidani L, Hull V, Fasih-Ahmad S, Esmaeilkhanian H, Wykoff CC, Rahmani E, Arnold CW, Zhou B, Zaitlen N, Gronau I, Sankararaman S, Chiang JN, Sadda SR, Halperin E. SLIViT: a general AI framework for clinical-feature diagnosis from limited 3D biomedical-imaging data. Res Sq. 2023 Nov 21:rs.3.rs-3044914. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3044914/v2. Update in: Nat Biomed Eng. 2025 Apr;9(4):507-520. doi: 10.1038/s41551-024-01257-9. PMID: 38045283; PMCID: PMC10690310. [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10690310/]